Conservators artfully restore painting

Techniques include blend of traditional and modern

Pitt-Bradford is restoring a lost 19th century masterwork painting that hung in the Emery Hotel. In 1964, the hotel was reincarnated as one of the university’s first residence halls. Once “The Emery” became a dormitory, the painting was stashed for safe keeping and forgotten for 55 years. In his final installment, conservators explain the art and science of the painting’s restoration.

CONSERVATORS ARTFULLY RESTORE PAINTING

Restoring “A Venetian Promenade,” the large oil painting found in a Bradford warehouse, has been part art and part science.

All things considered, the painting – which measures 15 feet wide by a little more than 8.5 feet tall in its ornate frame -- wasn’t in as bad shape as conservators feared it would be when it was found in the Carl E. Swanson and Sons warehouse, 55 years after being placed there by Pitt-Bradford.

Forgotten after that time, the painting – although well-crated -- endured changes in temperature and humidity that caused paint loss before being “rediscovered” by the current warehouse owner, Al Swanson.

After an initial examination of the painting, Patricia Colosimo, director of arts programming for Pitt-Bradford, found a conservator, Jeffrey Johnson of Johnson & Griffiths Studio in Harrisburg, to evaluate the condition and merit of the painting.

Meanwhile, Colosimo and Rick Esch, vice president of business affairs, used information on the painting to research the 19th century Italian artist, Tommaso Juglaris, and how the painting came to Bradford via Bradford oil millionaire Pennsylvania Sen. Lewis Emery.

The university hired Johnson to restore both the artwork and its ornate gilt frame. Johnson returned in summer to stabilize the painting. With oil paintings such as this, tinted oil was layered on the canvas and allowed to dry in layers. Over time, bending and moisture can come between the paint and the canvas, separating them.

To keep large pieces of paint from falling off the canvas, Johnson inserted a fine, medical grade needle between the paint layer and the canvas and injected conservation-grade adhesive.

“The paint film itself held together,” Johnson explained, “but it was detached from the canvas.”

With the paint securely in place, he took the painting and its frame to his workshop in Harrisburg, where he removed the canvas from its stretcher, cleaned the existing paint and filled in where paint is missing.

Paintings of the time were regularly finished with a coat of varnish applied after the top of the paint film after it had completely dried. The varnish – often called a sacrificial layer – protected the surface of the painting and could be removed without damaging the paint below.

Over many years, the varnish yellows, changing the appearance of the colors in the painting. Using their knowledge of the probable varnishes used at the time the painting was originally painted, Johnson and his assistant, Jacintha Clark, carefully applied various solvents to small test patches to see what would remove the varnish safely to reveal the painting’s true colors beneath. As they removed the varnish, decades of dirt and atmospheric grime went with it.

In order to work on a piece so large, Johnson had to build a new table in his studio. While cleaning and restoring the center-most parts of the painting, he said, conservators laid foam on the canvas and sat on it.

“It was a drastic change,” he said of the cleaned painting. “It looks as close to the way he painted it as it can. The painter’s colors have come back.”

After removing varnish and other old repair work down to the original paint, Johnson applied a new thin coating of varnish to preserve the original work.

Next, the team evened out the painting’s surface. Johnson explained that oil paint is applied in layers that can be as thick as a few sheets of paper. Just like a wall with peeling paint needs to be spackled, Johnson and Clark built up the surface before concocting historically accurate pigments to repaint in the missing parts.

When exposed under black light, each newly painted part glows, which can show conservators of the future where repairs were made.

Johnson then reinforced the brittle, original canvas by gluing it to a new piece of canvas using reversible thermoplastic adhesives.

“We actually laid the painting face down on our conservation table, applied a solvent-based adhesive, then laid the new canvas with its adhesive onto the original canvas,” Johnson explained.

“We carefully and methodically ironed the back of the new canvas to heat both of the adhesives to right around 150 degrees. We constantly monitored the temperature of the canvas with an infrared thermometer as we ironed to make sure we were not getting the mix too hot, which could damage the original paint film. As the adhesives cool, they become one, but always reversible at around 150 degrees.”

When “A Venetian Promenade” first arrived in America with Juglaris, it did so without a frame. The painter transported the large canvas rolled up. At some point, the painting obtained an American-made gilt frame that extends nearly a foot on each side. Its base is wood covered with ornate three-dimensional patterns made of cast plaster.

Through the years, some of the plaster elements got wet in the warehouse and fell from the frame, leaving unornamented bare wood. Fortunately, the warehouse leaks did not drip onto the painting itself.

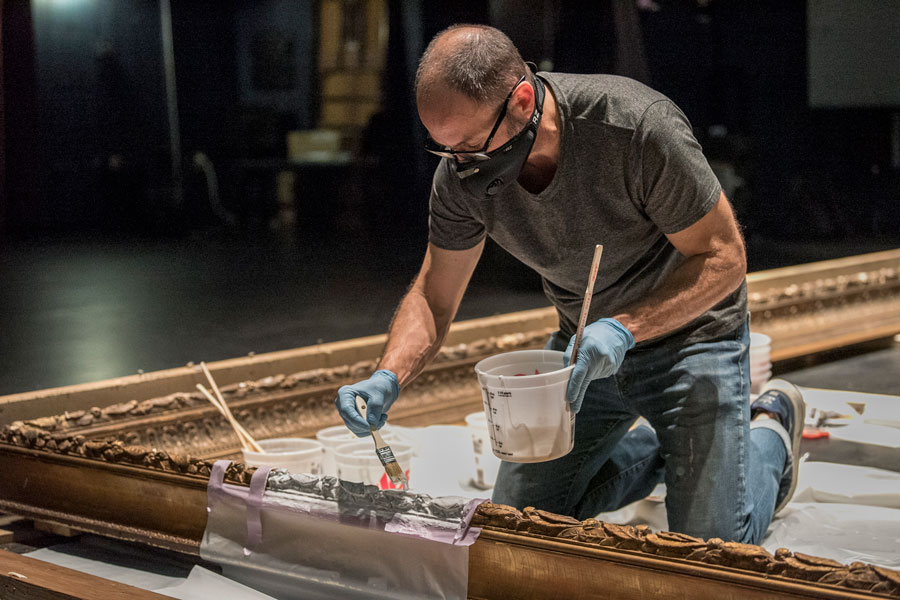

Last month, Johnson and his assistant, returned to Bradford with the painting and the frame. While Clark continued to paint in the bare spots on the canvas, Johnson created silicon molds of parts of the frame that can be used to create replacements for the missing ornamentation.

Later this month, Johnson and Clark will return to Pitt-Bradford to finish repairing and cleaning the frame, much of which is gilded – a process by which a fine coat of gold covers something.

Cleaning the gilt can be even trickier than cleaning the painting since artists and furniture makers evolved many techniques over the years. In some places where the gilt began to wear, it was covered with gold paint. The paint looked great at first, but discolored with age.

Once the painting and frame are restored, the science turns to the engineering of hanging such a large painting securely in the KOA Speer Lobby of Blaisdell Hall on the university’s campus, where it will be permanently displayed.

“We’re very excited to see this beautiful piece of artwork restored to its original brilliance and hanging in Blaisdell Hall,” said Dr. Catherine Koverola, Pitt-Bradford’s president, “which will be a constant reminder of Pitt-Bradford’s longstanding connection to the community.”

The painting will not only provide a valuable link between the campus and Bradford’s own gilded age of oil millionaires, but also serve as a teaching tool for Pitt-Bradford students as well as those from the community. Under black light, students will be able to see areas where the painting has been worked on.

A video documentary will detail the restoration and history of the piece.

The university plans to have an event to celebrate its new installment and show the documentary when it is safe to do so.

--30--