Professor researches non-coding DNA

Students taking part in finding molecules to help immune system

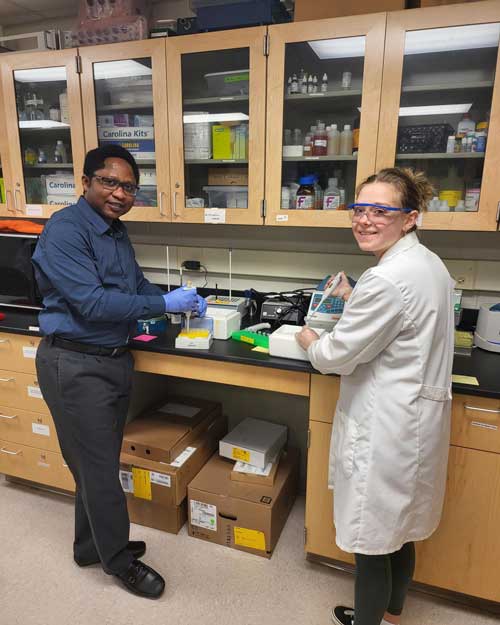

The fruits of Dr. Lanre Morenikeji and Ana Grytsay’s summer labor are stored in a freezer at -80 degrees Celsius.

They are strands of non-coding RNAs that the sophomore chemistry major separated from complete bovine RNA during five weeks this summer as part of research directed by Dr. Lanre Morenikeji, assistant professor of biology.

These RNAs are tiny molecules produced in the body that can help regulate mammalian immune response to microbes that cause disease.

Not long ago, the DNA the non-coding RNA is produced from was considered “junk DNA” unused by the body, Morenikeji explained. However, technological advances in genome sequencing have started giving scientists a better understanding of what might activate some of these RNAs to protect the body under stress.

But there is no way to predict how each tiny bit of RNA synthesized from DNA will affect a body until it is individually tested. It is an imposing task, but one that leaves lots of opportunities for researchers like Morenikeji.

Like astronomers divvying the sky up into tiny portions to study, biologists can consult and record in a worldwide registry which bits of unexplored DNA they are testing in the cells of mammals.

Grytsay’s tiny bits of RNA will be stored until another student this fall has a chance to grow the cells needed. In order to grow the cells at Pitt-Bradford, Morenikeji needed a new CO2 incubator. He recently won a $25,000 Pitt Momentum Fund Seeding Award and a partial match of $20,000 from Pitt-Bradford paid for the incubator and other equipment, student salaries for undergraduate researchers, supplies such as lab-grown mammal tissues and chemicals used to extract the RNA from cells.

“I like to break new ground,” Morenikeji said. He reads extensively to find gaps in the current knowledge that he can research with his undergraduate students. He is beginning his second year teaching at Pitt-Bradford but has already achieved success as a professor researching with undergraduates at Hamilton College, a small teaching-focused college in upstate New York, publishing with his students in the scientific journals such as Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology and Scientific Reports, among others.

He is prepared to hire a student to work with him growing cells in which to test the interactions of the RNA Grytsay extracted. He is willing to work with more students if they are interested.

After growing the cells needed for the next step of this project, students will transfect some of them with the tiny bits of RNA packaged in a vector DNA, looking for a change in the cell caused by the introduction of new molecules.

With literally billions of pairs of DNA previously thought of as junk to evaluate, Morenikeji has an endless need for students interested in research.

Grytsay said she would like to work more on the project and that it changed her perspective on studying biology, which previously she had thought of as a necessity for her goal of attending medical school.

“I think everyone should do research,” she said. “The work was very satisfying, and it opened up my eyes a lot more about what I want to do. I didn’t realize that I would like it as much as I did. It was a very eye-opening situation. The thing that I enjoy the most is learning new things, and when you are doing research, you are constantly learning new things. It brought forward another form of teaching for me.

“Professor Lanre would always tell me that he wanted to make me a great candidate for my life, whatever I choose to do after this. And that’s when I gained a really great appreciation for him as a professor.”

In the spring, Morenikeji worked with Olubumi Braimah, a 2022 graduate who is attending the University of Kansas School of Medicine this fall.

--30--