Student researchers want to know what’s special about honey

In their native Nepal, putka honey ascribed medicinal properties

When Heaman Dhimal and Alisha Khadka were children in Nepal, there was one cure for all their childhood illnesses – honey.

Now, as biology students at Pitt-Bradford, they want to find out whether their elders were right about the putka honey of their childhoods having special medicinal properties.

They’re not alone. Several other researchers have recently looked into the cultural use of the honey as medicine and how its sales affect the livelihood of Himalayan communities. Now 7,500 miles from where they grew up, Dhimal and Khadka are doing their own research to see why the putka honey is special.

Dhimal and Khadka both came to the United States as children as part of a refugee resettlement program. They both attended high school and met each other in Harrisburg, which has become a hub for the Bhutanese refugee community.

Dhimal’s family is part of a large ethnic minority called Lhotshampas who settled in southern Bhutan in the late 19th century to clear forest, create rice fields and work them. They had come from Nepal and spoke Nepalese. In 1958, Bhutan passed a citizenship act that gave them full citizenship. More policies encouraged intermarriage and moving to other parts of the country.

But in 1985, a new citizenship act stiffened the requirements to become a naturalized citizen and created conditions under which citizenship could be revoked, including being disloyal to the king, country or people of Bhutan.

Soon Bhutan began requiring that Lhotshampas prove that they had paid taxes and wear the traditional dress of the majority. Schools stopped teaching in Nepalese.

As the situation in Bhutan deteriorated and persecution increased, more Lhotshampas began to leave the country. They were not welcomed by India, which occupies a tongue of land between Bhutan and Nepal, and so they kept going back to the country of their ancestors.

Seven Bhutanese refugee camps were created in the subtropical lowlands of Nepal, where Dhimal grew up taking putka honey and attending school with ambitious standards in the camps.

Dhimal’s father was a honey harvester, climbing trees barefoot to retrieve the honey from wild bees. He was also a farmer and grew up taking care of cows and goats. He did not have the chance to attend school.

Dhimal’s parents chose to take advantage of the United Nations Human Rights Commission’s relocation program and join the increasing number of Bhutanese being resettled, including tens of thousands who came to the United States.

“They wanted me to get an education,” Dhimal said. “That’s why they came here.”

Dhimal has only vague memories of coming to the United States at the age of 6. He remembers new smells and that it was raining when his family was dropped off at their apartment in Harrisburg. “That was the first time I’d seen a car,” he said.

To learn English, he watched PBS Kids, especially “Curious George.”

“You know The Man with the Yellow Hat?” Dhimal asked, referring to the character who cares for the mischievous little monkey named George. “He would explain things to Curious George, and he was explaining them to me, too.”

Although Khadka’s mother is Lhotshampa, her father is Nepalese, and she grew up in a small village in Nepal. She said her parents always emphasized education, and she attended a boarding school.

“My dad used to make me study all of the time,” she said.

Khadka’s mother married at 19 and moved out of a refugee camp and into the village of Khadka’s father. They lived in a two-story concrete house. Khadka’s father fixed cars, and her mother had a little convenience store. Although she lived outside of the refugee camps, Khadka’s mother still had refugee status.

Eventually, Khadka’s mother decided to follow relatives and resettle in the United States when Khadka was 13. Khadka said she “just learned” English. “I had to learn,” she said. “I was used to studying.”

Both students said they have always wanted to be doctors. Khadka applied and was accepted to other colleges, but they were too expensive. That’s when Dhimal told her about Pitt-Bradford, where he was an accepted student, and its substantial financial aid, a good biology program and opportunities such as undergraduate research that improve chances for medical school acceptance.

Both have taken advantage of all the campus has to offer – not only research, but also a study abroad trip last summer to Graz, Austria, with Orin James, assistant professor of biology, to compare health care in Austria and Slovenia to that in the United States.

Khadka loved Austria. “It’s so beautiful,” she said. “It’s all clean.”

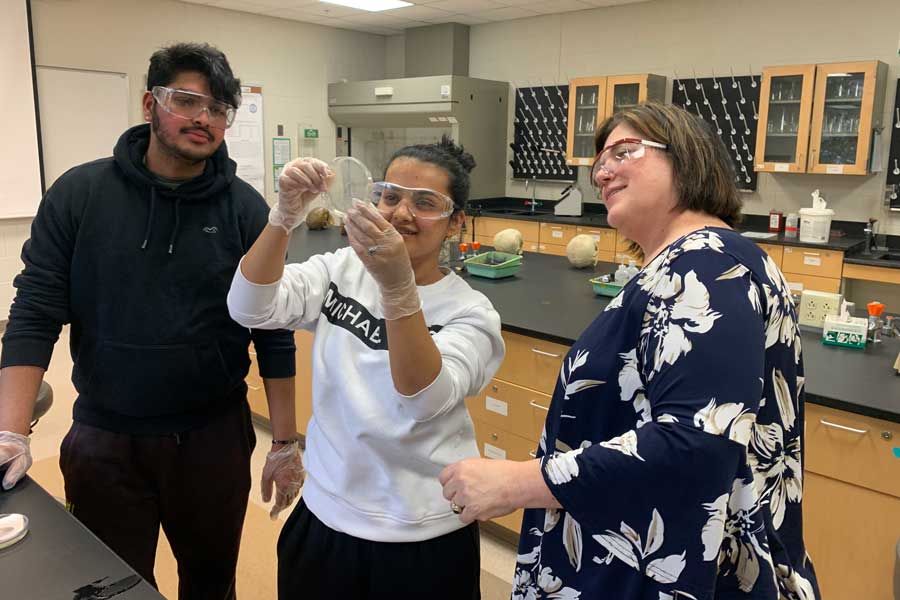

Back in the lab with her research mentor, Dr. Robin Choo, assistant professor of biology, Khadka swabbed a diluted mixture of honeys and nutrient broth onto petri dish plates. She is evaluating the antimicrobial properties of putka honey against other honeys, such as domestic, wild, raw and pasteurized. After swabbing the plates, she labeled each and puts them in the incubator.

Dhimal is taking a different tack, working with Melissa Odorisio, laboratory administrator, to extract chemicals from the putka in search of the root of its medicinal properties.

Both Khadka and Dhimal plan to present their findings at Pitt-Bradford’s annual Undergraduate Scholarship and Research Day April 15.

--30--