Make Our Day

Makerspace lets students channel their inner inventors

On a winter night shortly after the George B. Duke Engineering and Information Technologies Building opened, the makerspace was humming.

Aaron Straus, the university’s inaugural creative engineering coordinator, was showing students how to use a 3D laser printer to make – well, whatever they wanted.

At a sewing machine about 24 feet away on the other side of the room, a student was helping another hem her gown for the upcoming winter formal. At a table nearby, a student using a wheelchair maneuvered easily under a work station to work on another garment for the formal, one that let them design an outfit that not only worked with their wheelchair but also mixed masculine and feminine styles.

More students wandered in the open door, saying that Straus had invited them for coffee. (Homemade lattes and cappuccinos being one of the approaches he uses to help students feel welcome to the space for the first time.)

One of them, Jameela Joseph, a senior biology major from Harrisburg, Pa., picked up items lying out on the tables to examine them with interest. These items were the next crumb Straus had dropped on the trail. Each is a project created by students Straus worked with in a secondary school environment – a xylophone made of wood and copper tubing cut with a band saw; a prosthetic hand made up of parts printed on the 3D printers; a miniature robot arm made up of parts printed on the 3D printers and wired to a circuit board printed in the makerspace as well; a crude wooden pinball machine that lights up when a steel ball connects a circuit; and (because … college students) a laser tag set.

If the makerspace had existed earlier in her college career, Joseph mused, she might have switched her major.

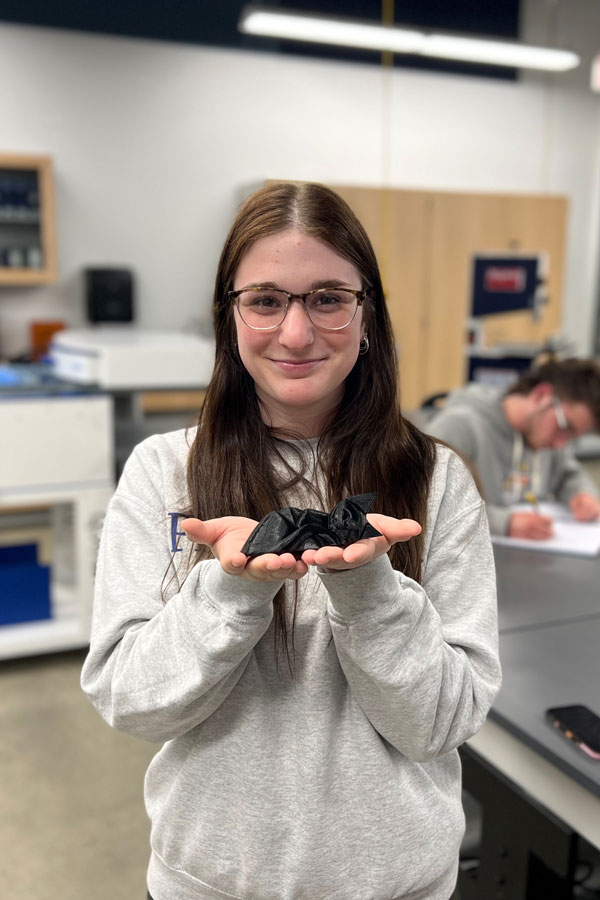

Another senior biology major, Kimberly Goodwin of Aurora, Ill., echoed Joseph’s thoughts as she printed out a 3D soccer ball. Her mom had studied both industrial engineering and nursing. Holding the bright orange soccer ball, she pondered that if she had been exposed to a space like the makerspace earlier, perhaps she would have studied engineering herself.

Such is the power of the makerspace.

What is a makerspace?

If you don’t make it often to the public library or have children in school, you might not be familiar with the idea of makerspaces, which are public spaces that provide technical tools for the creation of physical objects.

In the early 2000s, public libraries led the movement by investing in physical spaces that offered 3D printers, laser cutters and microcomputers for use by patrons. As technology advanced and prices for the resources dropped, more libraries created makerspaces that encouraged sharing knowledge and collaboration. In the utopian atmosphere of public libraries, the culture became as much a part of makerspaces as the gadgets.

Soon educators realized the potential of makerspaces for encouraging creativity, teaching problem solving, engaging students, and promoting science, technology, engineering, and math, and they began appearing in public schools. Many of today’s college students have already worked in makerspaces before arriving on campus.

How does the makerspace benefit students?

In short, the makerspace allows more students to apply their learning to creating physical objects, an act that reinforces their learning and presents the practical challenges of production. Straus hopes that it’s not long before he has theater students creating props and anatomy students 3D printing models. Instead of using ink, these “printers” layer materials – ranging from biodegradable plastic to carbon fiber – to create three-dimensional models. Engineering students can use these printers to create prototypes of their designs. A circuit board printer, soldering station and laser engraver give students even more options.

When Matthew Copfer, a senior sociology student from Union City, Pa., showed up in the makerspace early in its first semester, it changed the trajectory of his future.

An enthusiastic player of Dungeons & Dragons and a Pokémon fan, Copfer wanted to construct a sculpture of his favorite character from the Pokémon show that would also be a fair-play dice roller for D&D. With help from Straus, Copfer created the roller, but once he used it, he discovered there were changes he would like to make.

“I’ve been working with Professor Straus to improve it,” he said. Thus began his journey of tinkering –prototyping, printing and improving – to advance the roller’s design. It’s a process often referred to as rapid prototyping.

“I thought it was a great way to learn something new, and this is the perfect place for it,” Copfer said.

His interaction with engineering students in the neighboring machine shop ignited his interest in another opportunity: a 12-week intensive summer machinist and CNC (computer numerical control) program at the University of Pittsburgh at Titusville’s Education and Training Hub. Consequently, he joined a cohort of Pitt-Bradford engineering students commuting to the program this summer.

For senior computer information systems and technology student Tyler Babinski, the makerspace allowed him to realize a project that would otherwise remain a concept-- building a weather station capable of transmitting data to the National Weather Service.

Babinski’s father grew up in rural Virginia and retired to farm after a military career, so Babinski had firsthand experience with unpredictable weather patterns affecting crops. “I’ve seen the crops wither away,” he said. “[Bradford] really lacks access to its own [weather] data. After the [Bradford Regional] airport, there’s nothing.”

So, he set out to build a weather station with sensors that will collect data every 30 seconds to report to the Civil Weather Observation Program.

“I went to [Straus] with a crazy idea, and he said, ‘Sure, of course.’ Up until right now, I never could have done this.” One of the problems at hand was creating a box that would protect the station while also allowing it to measure the weather.

Using the resources in the makerspace, Babinski designed and printed a protective box for the weather station capable of withstanding harsh weather conditions.

“This building will be where awesome ideas come to life,” he said.

What’s in the space?

The makerspace is named in memory of Harry R. Halloran Jr. and in honor of Halloran Philanthropies and American Refining Group Inc. In December, Halloran Philanthropies made a $700,000 gift to the university to furnish the makerspace and the fluid dynamics lab.

The makerspace now holds basic and more advanced 3D printers, such as those that can print in multiple colors, multiple materials and carbon fiber. One prints items with independent articulation, such as a model car with wheels that spin, without having to print the items separately and then assemble them.

There is a vacuum former, laser engraver and circuit board printer as well as a sewing machine and T-shirt press. For wood and metal, students can work with Straus in the adjacent machine shop and fabrication lab to precision cut anything from a dowel to a sheet of steel.

Goodwin, the biology major who printed a 3D soccer ball, said, “You really can make anything.”